How Workflow execution looks like?¶

Workflow execution is a complex subject, but you don’t need to understand every detail to get started effectively. Grasping some basic concepts can significantly speed up your learning process with the Workflows ecosystem. This document provides a clear and straightforward overview, designed to help you quickly understand the fundamentals and build more powerful applications.

For those interested in a deeper technical understanding, we invite you to explore the developer guide for more detailed information.

Compilation¶

Workflow execution begins with compiling the Workflow definition. As you know, a Workflow definition is a JSON document that outlines inputs, steps, outputs, and connections between elements. To turn this document into an executable format, it must be compiled.

From the Execution Engine’s perspective, this process involves creating a computation graph and checking its integrity and correctness. This verification step is crucial because it helps identify and alert you to errors early on, making it easier and faster to debug issues. For instance, if you connect incompatible blocks, use an invalid selector, or create a loop in your workflow, the compiler will notify you with error messages.

Once the compilation is complete, it means your Workflow is ready to run. This confirms that:

-

Your Workflow is compatible with the version of the Execution Engine in your environment.

-

All blocks in your Workflow were successfully loaded and initialized.

-

The connections between blocks are valid.

-

The input data you provided for the Workflow has been validated.

At this point, the Execution Engine can begin execution of the Workflow.

Data in Workflow execution¶

When you run a Workflow, you provide input data each time. Just like a function in programming that can handle different input values, a Workflow can process different pieces of data each time you run it. Let's see what happens with the data once you trigger Workflow execution.

You provide input data substituting inputs' placeholders defined in the Workflow. These placeholders are referenced by steps of your Workflow using selectors. When a step runs, the actual piece of data you provided at that moment is used to make the computation. Its outputs can be later used by other steps, based on steps outputs selectors declared in Workflow definition, continuing this process until the Workflow completes and all outputs are generated.

Apart from parameters with fixed values in the Workflow definition, the definition itself does not include actual data values. It simply tells the Execution Engine how to direct and handle the data you provide as input.

What is the data?¶

Input data in a Workflow can be divided into two types:

-

Batch-Oriented Data to be processed: Main data to be processed, which you expect to derive results from (for instance: making inference with your model)

-

Scalars: These are single values used for specific settings or configurations.

Thinking about standard data processing, like the one presented below, you may find the distinction between scalars and batch-oriented data artificial.

def is_even(number: int) -> bool:

return number % 2 == 0

You can easily submit different values as number parameter and do not bother associating the

parameter into one of the two categories.

is_even(number=1)

is_even(number=2)

is_even(number=3)

The situation becomes more complicated with machine learning models. Unlike a simple function like is_even(...),

which processes one number at a time, ML models often handle multiple pieces of data at once. For example,

instead of providing just one image to a classification model, you can usually submit a list of images and

receive predictions for all of them at once performing the same operation for each image.

This is different from our is_even(...) function, which would need to be called separately

for each number to get a list of results. The difference comes from how ML models work, especially how

GPUs process data - applying the same operation to many pieces of data simultaneously, executing

Single Instruction Multiple Data operations.

The is_even(...) function can be adapted to handle batches of data by using a loop, like this:

results = []

for number in [1, 2, 3, 4]:

results.append(is_even(number))

In Workflows, usually you do not need to worry about broadcasting the operations into batches of data - Execution Engine is doing that for you behind the scenes, but once you understood the role of batch-oriented data, let's think if all data can be represented as batches.

Standard way of making predictions from classification model is be illustrated with the following pseudo-code:

images = [PIL.Image(...), PIL.Image(...), PIL.Image(...), PIL.Image(...)]

model = MyClassificationModel()

predictions = model.infer(images=images, confidence_threshold=0.5)

You can probably spot the difference between images and confidence_threshold.

Former is batch of data to apply single operation (prediction from a model) and the latter is parameter

influencing the processing for all elements in the batch and this type of data we call scalars.

Nature of batches and scalars

What we call scalar in Workflows ecosystem is not 100% equivalent to the mathematical term which is usually associated to "a single value", but in Workflows we prefer slightly different definition.

In the Workflows ecosystem, a scalar is a piece of data that stays constant, regardless of how many elements are processed. There is nothing that prevents from having a list of objects as a scalar value. For example, if you have a list of input images and a fixed list of reference images, the reference images remain unchanged as you process each input. Thus, the reference images are considered scalar data, while the list of input images is batch-oriented.

To illustrate the distinction, Workflow definitions hold inputs of the two categories:

-

Scalar inputs - like

WorkflowParameter -

Batch inputs - like

WorkflowImage,WorkflowVideoMetadataorWorkflowBatchInput

When you provide a single image as a WorkflowImage input, it is automatically expanded to form a batch.

If your Workflow definition includes multiple WorkflowImage placeholders, the actual data you provide for

execution must have the same batch size for all these inputs. The only exception is when you submit a

single image; it will be broadcast to fit the batch size requirements of other inputs.

Steps interactions with data¶

If we asked you about the nature of step outputs in these scenarios:

-

A: The step receives only scalar parameters as input.

-

B: The step receives batch-oriented data as input.

-

C: The step receives both scalar parameters and batch-oriented data as input.

You would likely say:

-

In option A, the output will be non-batch.

-

In options B and C, the output will be a batch. In option C, the non-batch-oriented parameters will be broadcast to match the batch size of the data.

And you’d be correct. Knowing that, you only have two more concepts to understand to become Workflows expert.

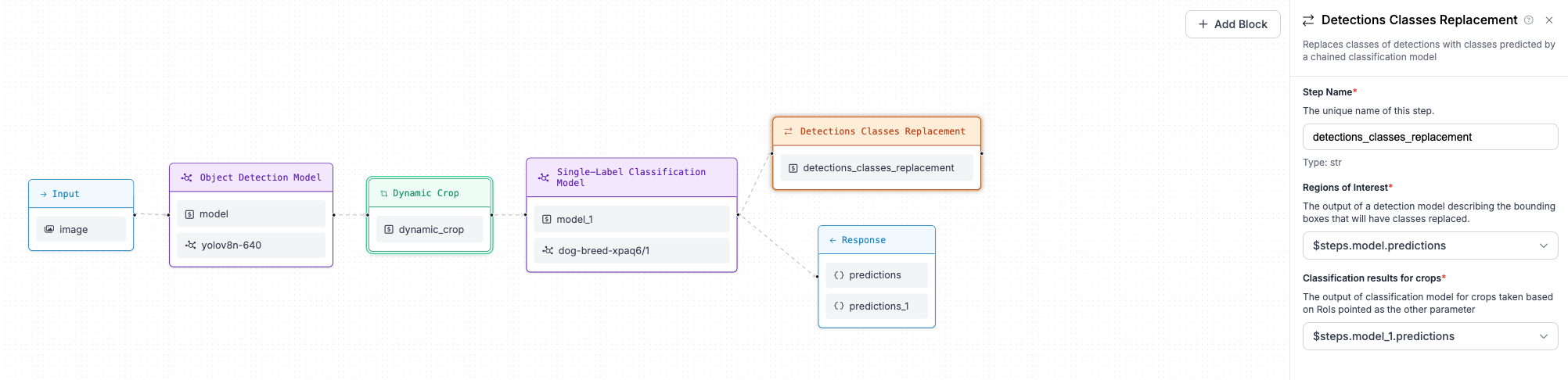

Let’s say you want to create a Workflow with these steps:

-

Detect objects in a batch of input images.

-

Crop each detected object from the images.

-

Classify each cropped object with a second model to add detailed labels.

Here’s what happens with the data in the cropping step:

-

You start with a batch of images, let’s say you have

nimages. -

The object detection model finds a different number of objects in each image.

-

The cropping step then creates new image for each detected object, resulting in a new batch of images for each original image.

So, you end up with a nested list of images, with sizes like [(k[1], ), (k[2], ), ... (k[n])], where each k[i]

is a batch of images with a variable size based on the number of detections. The second model (classifier)

will process these nested batches of cropped images. There is also nothing that stops you from going deeper

in nested batches world.

Here’s where it gets tricky, but Execution Engine simplifies this complexity. It manages the nesting of

data virtually, so blocks always receive data in a flattened, non-nested format. This makes it easier to apply

the same block, like an object detection model or classifier, regardless of how deeply nested your data is. But

there is a price - the notion of dimensionality level which dictates which steps may be connected, which not.

dimensionality level concept refers to the level of nesting of batch. Batch oriented Workflow inputs

have dimensionality level 1, crops that we described in our example have dimensionality level 2 and so on.

What matters from the perspective of plugging inputs to specific step is:

-

the difference in

dimensionality levelacross step inputs -

the impact of step on

dimensionality levelof output (step may decrease, keep the same or increase dimensionality)

Majority of blocks are designed to work with inputs at the same dimensionality level, not changing dimensionality of

its outputs, with some being exceptions to that rule. In our example, predictions from object-detection model

occupy dimensionality level 1, while classification results are at dimensionality level 2, due to the fact that

cropping step introduced new, dynamic level of dimensionality.

Now, if you can find a block that accepts both object detection predictions and classification predictions, you could

use our predictions together only if block specifies explicitly it accepts such combination of dimensionality levels,

otherwise you would end up seeing compilation error. Hopefully, there is a block you could use in this context.

Detections Classes Replacement block is designed to substitute bounding boxes classes labels with predictions from classification model performed at crops of original image with respect to bounding boxes predicted by first model.

Warning

We are working hard to change it, but so far the Workflow UI in Roboflow APP is not capable of displaying the

concept of dimensionality level. We know that it is suboptimal from UX perspective and very confusing but we

must ask for patience until this situation gets better.

Note

Workflows Compiler keeps track of data lineage in Workflow definition, making it impossible to mix

together data at higher dimensionality levels that do not come from the same origin. This concept is

described in details in developer guide. From the user perspective it is important to understand that if

image is cropped based on predictions from different models (or even the same model, using cropping step twice),

cropping outputs despite being at the same dimensionality level cannot be used as inputs to the same step.

Conditional execution¶

Let’s be honest—programmers love branching, and for good reason. It’s a common and useful construct in programming languages.

For example, it’s easy to understand what’s happening in this code:

def is_string_lower_cased(my_string: str) -> str:

if my_string.lower() == my_string:

return "String was lower-cased"

return "String was not lower-cased"

But what about this code?

def is_string_lower_cased_batched(my_string: Batch[str]) -> str:

pass

In this case, it’s not immediately clear how branching would work with a batch of strings. The concept of handling decisions for a single item is straightforward, but when working with batches, the logic needs to account for multiple inputs at once. The problem arises due to the fact that independent decision must be made for each element of batch - which may lead to different execution branches for different elements of a batch. In such simplistic example as provided it can be easily addressed:

def is_string_lower_cased_batched(my_string: Batch[str]) -> Batch[str]:

result = []

for element in my_string:

if element.lower() == my_string:

result.append("String was lower-cased")

else:

result.append("String was not lower-cased")

return result

In Workflows, however we want blocks to decide where execution goes, not implement conditional statements inside block body and return merged results. This is why whole mechanism of conditional execution emerged in Workflows Execution engine. This concept is important and has its own technical depth, but from user perspective there are few things important to understand:

-

some Workflows blocks can impact execution flow - steps made out of those blocks will be specified a bunch of step selectors, dictating possible next steps to be decided for each element of batch (non-batch oriented steps work as traditional if-else statements in programming)

-

once data element is discarded from batch by conditional execution, it will be hidden from all affected steps down the processing path and denoted in outputs as

None -

multiple flow-control steps may affect single next step, union of conditional execution masks will be created and dynamically applied

-

step may be not executed if there is no inputs to the step left after conditional execution logic evaluation

-

there are special blocks capable of merging alternative execution branches, such that data from that branches can be referred by single selector (for instance to build outputs). Example of such block is

First Non Empty Or Default- which collapses execution branches taking first value encountered or defaulting to specified value if no value spotted -

conditional execution usually impacts Workflow outputs - all values that are affected by branching are in fact optional (if special blocks filling empty values are not used) and nested results may not be filled with data, leaving empty (potentially nested) lists in results - see details in section describing output construction.

Output construction¶

The most important thing to understand is that a Workflow's output is aligned with its input regarding batch elements order. This means the output will always be a list of dictionaries, with each dictionary corresponding to an item in the input batch. This structure makes it easier to parse results and handle them iteratively, matching the outputs to the inputs.

input_images = [...]

workflow_results = execution_engine.run(

runtime_parameters={"images": input_images}

)

for image, result in zip(input_images, workflow_results):

pass

Each element of the list is a dictionary with keys specified in Workflow definition via declaration like:

{"type": "JsonField", "name": "predictions", "selector": "$steps.detection.predictions"}

what you may expect as a value under those keys, however, is dependent on the structure of the workflow.

All non-batch results got broadcast and placed in each and every output dictionary with the same value.

Elements at dimensionality level 1 will be distributed evenly, with values in each dictionary corresponding

to the alignment of input data (predictions for input image 3, will be placed in third dictionary). Elements at

higher dimensionality levels will be embedded into lists of objects of types specific to the step output

being referred.

For example, let's consider again our example with object-detection model, crops and secondary classification model.

Assuming that predictions from object detection model are registered in the output under the name

"object_detection_predictions" and results of classifier are registered as "classifier_predictions", you

may expect following output once three images are submitted as input for Workflow execution:

[

{

"object_detection_predictions": "here sv.Detections object with 2 bounding boxes",

"classifier_predictions": [

{"classifier_prediction": "for first crop"},

{"classifier_prediction": "for second crop"}

]

},

{

"object_detection_predictions": "empty sv.Detections",

"classifier_predictions": []

},

{

"object_detection_predictions": "here sv.Detections object with 3 bounding boxes",

"classifier_predictions": [

{"classifier_prediction": "for first crop"},

{"classifier_prediction": "for second crop"},

{"classifier_prediction": "for third crop"}

]

}

]

As you can see, "classifier_predictions" field is populated with list of results, of size equivalent to number

of bounding boxes for "object_detection_predictions".

Interestingly, if our workflows has ContinueIf block that only runs cropping and classifier if number of bounding boxes

is different from two - it will turn classifier_predictions in first dictionary into empty list. If conditional

execution excludes steps at higher dimensionality levels from producing outputs as a side effect of execution -

output field selecting that values will be presented as nested list of empty lists, with depth matching

dimensionality level - 1 of referred output.

Some outputs would require serialisation when Workflows Execution Engine runs behind HTTP API. We use the following serialisation strategies:

-

images got serialised into

base64 -

numpy arrays are serialised into lists

-

sv.Detections are serialised into

inferenceformat which can be decoded on the other end of the wire usingsv.Detections.from_inference(...)

Note

sv.Detections, which is our standard representation of detection-based predictions is treated specially

by output constructor. JsonField output definition can specify optionally coordinates_system property,

which may enforce translation of detection coordinates into coordinates system of parent image in workflow.

See more in docs page describing outputs definitions